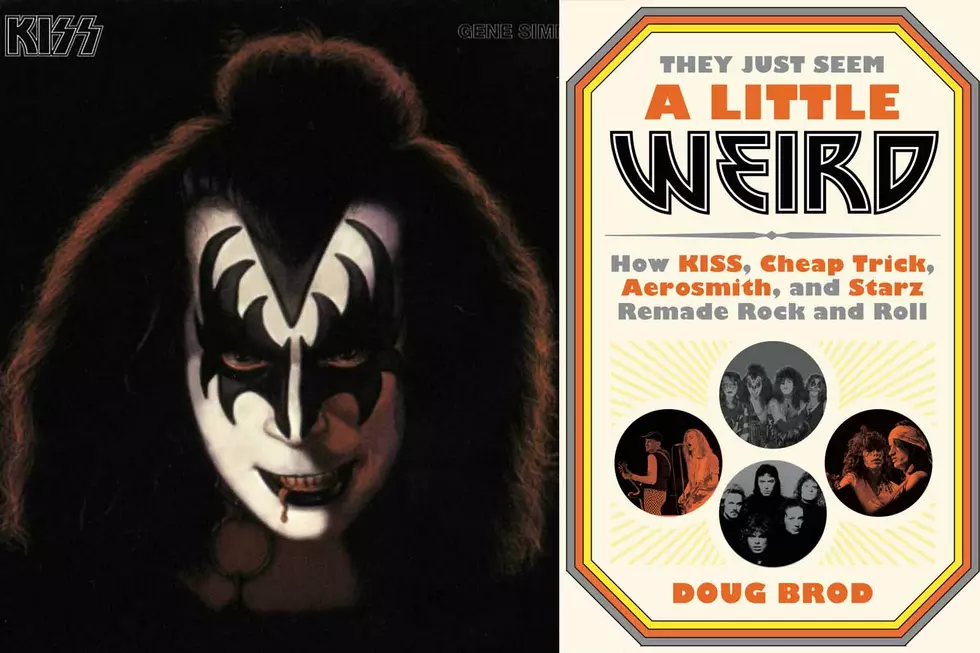

How Gene Simmons Recorded His 1978 Solo Album: Book Excerpt

Doug Brod's new book They Just Seem a Little Weird examines the intertwining histories of Kiss, Aerosmith, Cheap Trick and Starz to show how they paved the way for both hair metal and grunge. In the following excerpt, Brod delves into the recording of Gene Simmons' 1978 solo album, which featured guest turns by lead guitarists from the other three acts – Joe Perry, Rick Nielsen and Richie Ranno:

Simmons recorded the album’s basic tracks in around four weeks at the Manor, in the quaint village of Shipton-on-Cherwell, 65 miles northwest of London. The studio, then owned by Virgin Records magnate Richard Branson, was built in a sprawling 16th-century mansion, and its lush surroundings provided a comfortable living and work space for Simmons, Cher, her two kids, technicians, bodyguards, as well as the seasoned session pros — bassist Neil Jason, drummer Allan Schwartzberg, guitarist Elliott Randall, pianist Richard Gerstein (aka Richard T. Bear) — Simmons flew in from New York to form the core band. “We were all together in one place,” Jason says, “so it fostered a much more creative, fast-working environment.”

For the purposes of recording, Simmons and Delaney stationed the musicians in different parts of the house — the guitars and amps in one bedroom, Schwartzberg and his drums confined to the snooker room — with everyone communicating via mics and headphones. No rehearsals, no demos — and they worked out their parts on their own. “You’d get a lead sheet with the chords,” the drummer says, “and you’d scratch out your chart.”

While he enjoyed the overall experience, Schwartzberg did find himself on the receiving end of Simmons’s infamous imperiousness. “We’re all in the house,” he remembers. “We’ve been playing for days and days, and he’d say, ‘Drums, maybe the first bar you could come in with just bass drum.’ And, ‘Bass, just ...’ At one point we stopped him and said, ‘Gene, everybody here has a name.’” Sufficiently chastened, Simmons acquiesced to calling them by their names, but Schwartzberg suspects he would have preferred to continue his less personal approach.

Gerstein remembers Simmons, whom he met through Delaney, as a micro-manager who pushed people hard. “He was loud — he was an Israeli,” Gerstein says. “You had to come to the table and provide something or you weren’t around long.” Nearly two weeks into the session, with cabin fever setting in, he approached Simmons: “Man, you’ve got a girlfriend here. We’ve all been here for like 10 days — I’m sick of Rosie Palm and her five sisters.” Gerstein’s remark made him laugh, and the next day, after Simmons and Cher took off for a while, the keyboardist was shocked when a limousine pulled up in front of the Manor and out strode a bevy of attractive young women. “I knew what the tone of the evening was going to be when this one girl got out and she had on a Stiff Records T-shirt,” he says. “You remember their motto: ‘If It Ain’t Stiff, It Ain’t Worth a Fuck.’”

Returning to the states for overdubs, Simmons recorded many of his special guests at Hollywood’s Cherokee Studios and Manhattan’s Blue Rock Studio. Standing out among this diverse roster were three accomplished lead guitarists, all of them friends of Simmons’s and members of bands with whom Kiss shared stages and would be linked, by fans or by fate, for decades to come: Joe Perry of Aerosmith, Rick Nielsen of Cheap Trick, and Richie Ranno of Starz. And back in 1978, those three groups faced critical career junctures of their own.

Listen to Joe Perry on Gene Simmons' 'Radioactive'

Aerosmith were in free fall. Their smash albums, 1975’s Toys in the Attic and 1976’s Rocks, both produced by Jack Douglas, made them superstars, but their crippling drug habits (Perry and lead singer Steven Tyler had become known as “the Toxic Twins”), not to mention a punishing tour schedule, were taking their toll. The band’s latest record, Draw the Line, released in December 1977, was widely considered a creative misstep and commercial disappointment, and July 1978 saw the premiere of a rotten movie of their own, the star-spackled debacle Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

Perry was in Los Angeles when Simmons invited him over one night to hear some tracks that he thought the guitarist might want to play on. “We were buddies,” Perry has said. “Us and Kiss, we kind of came up side by side.” On arriving at Cher’s house at around 9 p.m., he was surprised to find the couple in bed in their pajamas: “I had changed out of my pajamas to come over.” (Around this time, he also helped Simmons out on a demo called “Mongoloid Man,” which never got finished, although a few bits ended up in subsequent songs.)

It was at his recording session for the Simmons album where Perry, who can be heard on “Radioactive,” has claimed he finally met and befriended the Cheap Trick guitarist, whom he had long admired. “I was sitting making use of the glass top of the pinball machine” — presumably, euphemistically, snorting cocaine — “and Rick Nielsen walked in,” Perry said. “I see this goofy-looking guy and it’s hard to miss him. He’s got Cheap Trick written on his fucking eyelids.” (Nielsen, however, insists he and Perry became acquainted well before this session.) Mitch Weissman recalls playing ping-pong with Nielsen during downtime, using the guitarist’s plectrums in place of balls.

Nielsen’s group were on the ascendant. Simmons, an early champion, went so far as to take Cheap Trick on the road the previous summer. At the end of April 1978, Cheap Trick would be heading to Japan to play what would become for them a very consequential string of dates. In May, they’d be releasing their third studio album, Heaven Tonight, featuring their first, if minor, radio hit, “Surrender,” with lyrics that famously name-check Simmons’s band (“Got my Kiss records out”) and offer a description of parents that became the title of this book.

“I was just asked to come in and add my two cents. I was honored to get asked,” says Nielsen, who played a predictably frantic and fantastic solo on “See You in Your Dreams,” a remake of a track off of Kiss's fifth studio LP, Rock and Roll Over, and the Simmons album’s rowdiest rocker. Cleverly, the first seven notes of Nielsen’s solo evoke “When You Wish Upon a Star,” foreshadowing the album’s closing track, an achingly sentimental cover of that same chestnut from Walt Disney’s Pinocchio. “He hired me because he wanted me to play like I play,” Nielsen says, explaining his M.O. “I’m not a studio guy, and I’m not what they already have, so I play with what I bring.” Simmons was particularly pleased with the guitarist’s contribution, jokingly saying in a promotional interview, “The guy sounds like Page, the best Page you ever heard: page nine, page 10.”

Listen to Rick Nielsen on Gene Simmons' 'See You in Your Dreams'

To show his appreciation, Simmons sent Nielsen a set of the four solo albums, which the guitarist never opened and kept in storage. On a 2013 episode of the junk-shop TV series American Pickers, he sold them for $200 to collector Frank Fritz. “I said, ‘Gene probably won’t like this, but here you go,’” Nielsen says. “Frank was such a fan. I think I’d have to go out and buy a record player anyhow.”

Starz, the second band [late Kiss manager Bill] Aucoin signed to his management company, opened many times for Aerosmith, played a show with Kiss in 1976, and scored a minor hit in May 1977 with the Jack Douglas–produced “Cherry Baby,” which peaked at No. 33 on the Billboard singles chart. But they too were in a downward spiral, owing to Capitol Records’ neglect (or so some members say) and a violent outburst at a promo-film shoot.

Richie Ranno says his participation on Simmons’s album came to him in a premonition. It was 1975 and Kiss were determined but struggling, not yet the arena-filling monsters that the Alive! double LP would create when it took off later that year. Starz were in Detroit, rehearsing with Sean Delaney, who early on had a big hand in their creative decisions as well. “I had this weird dream that Gene made a solo album,” Ranno told Delaney one morning, “and the only thing on the cover was his face. And I played on it.” Three years later, while writing songs for Starz’s Coliseum Rock, Ranno got word of the four albums and was bummed that he hadn’t been asked to play on Simmons’s. A few weeks before he was to head to Toronto to track what would turn out to be his band’s final album, he got a call from Delaney; apparently Simmons didn’t love either of the solos that Joe Perry and “Skunk” Baxter had added to “Tunnel of Love.” Simmons initially requested Nils Lofgren, who was then enjoying a successful solo career after a fruitful association with Neil Young, as a replacement, but Delaney recommended Ranno.

“I said, ‘Sean, you remember my dream, right?’ ” Ranno recalls. “And he said, ‘Yes, I do!’ So I went in. I’m the only guitar player on that song — not Perry and not Baxter — but they never changed the credits, which list all three of us.” Perry, for his part, didn’t dispute Ranno’s claim. “When I listened to the track,” he said, “I had trouble discerning whether I even played on it.”

In a promotional interview for the album, Simmons said Ranno’s solo came about when the guitarist “just happened by one day and said, ‘What does that sound like?’ I said, ‘I don’t know, give it a try.’ ” For their troubles, Nielsen and Ranno got their names misspelled “Neilson” and “Ritchie” on the back cover of the original pressing, where Simmons also thanks Steven Tyler and Doobie, presumably Ranno’s bandmate Joe X. Dubé, who played on demos for the KISS bassist. (Keeping things all in the Aucoin family, Ranno bandmate Brendan Harkin contributed guitar to Peter Criss’s solo album.)

Excerpted from THEY JUST SEEM A LITTLE WEIRD: How KISS, Cheap Trick, Aerosmith, and Starz Remade Rock and Roll by Doug Brod. Copyright © 2020. Available from Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Kiss Albums Ranked

Why Don't More People Love This Aerosmith Album?

More From Beach Radio