NJ’s top prosecutor wants end to mandatory minimum drug sentences

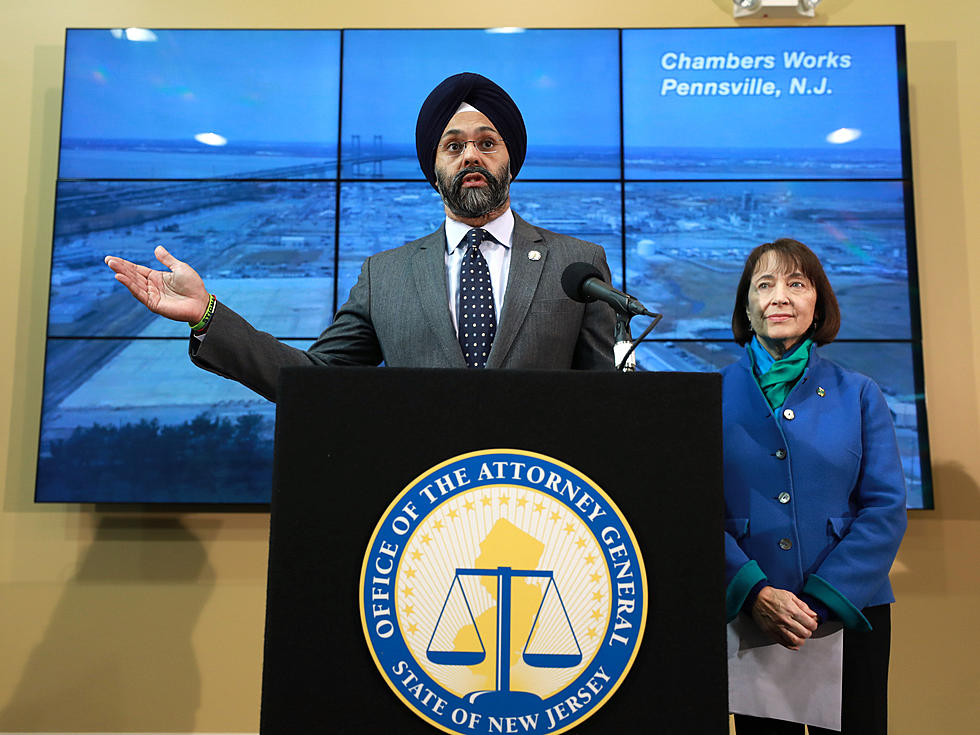

TRENTON — Attorney General Gurbir Grewal is calling for an end to state laws requiring mandatory minimum sentences for non-violent drug crimes.

In an interview with New Jersey 101.5 on Tuesday, Grewal said it's "about time that New Jersey caught up with a lot of other states that have made progressive reforms" on mandatory minimums, not just for non-violent drug crime, but also non-violent property offenses.

In an essay published in some of the state's newspapers this week, Grewal said: "One of the first lessons I learned as a young prosecutor was also one of the most important: that our success is measured not by the number of people we convict, or the length of the prison sentences we obtain, but by whether justice is done in each and every case."

A mandatory minimum sentence means that an offender must serve the entire mandatory portion of his or her sentence before becoming eligible for parole consideration.

Mandatory minimum sentences cannot be reduced by earned credits, such as commutation, minimum security, or work. As of January 2018, 75% of all adult offenders have mandatory minimum terms, with the average being 5.5 years, according to Department of Corrections data.

"In 1987, at the height of America’s 'War on Drugs,' New Jersey followed the lead of other states and enacted laws requiring strict mandatory prison terms for certain drug crimes. Well-intentioned as they may have been, the laws didn’t do a particularly good job of distinguishing between high-level traffickers and street-corner dealers, and over the past three decades, tens of thousands of New Jersey residents have been subject to their broad reach," Grewal wrote.

According to Crossroads NJ, a project of The Fund for New Jersey, 11% of the state's 7,990 prisoners in 1982 were serving mandatory minimum terms. Today, 74% of New Jersey's 20,489 prisoners — more than 15,000 people — are serving mandatory minimum sentences.

"Most problematic are the provisions that automatically render certain offenders ineligible for parole for long portions of their prison sentences, effectively forcing the state to keep even non-violent inmates locked up long after it’s clear they no longer pose a threat to the community," Grewal wrote.

"Every dollar New Jersey spends imprisoning non-violent drug offenders for longer than necessary is a dollar we’re not spending on crime prevention, addiction treatment, or reentry efforts. But more importantly, these drug laws have had devastating social costs, especially in our African-American communities, which have borne the brunt of New Jersey’s mandatory drug sentences," he added.

He mentioned other states that have reformed their mandatory minimum sentencing laws, including Texas, South Carolina, and Indiana.

"Study after study has shown these reforms effectively reduced state prison populations—and did so without prompting a rise in crime rates," Grewal said.

The nationwide advocacy organization, FAMM, also has an online list of state-by-state sentencing reforms, and said it is making progress in Arizona, Florida, North Carolina and Pennsylvania.

On Tuesday, Grewal said by not keeping non-violent offenders in prison, the cost savings can be reinvested in rehabilitating folks and helping them re-enter society.

In his written piece, he said not all mandatory minimum sentences are "ill-conceived," as "in New Jersey, we require judges to impose prison terms for a handful of other serious crimes—mostly offenses involving violence, illegal gun use, child sex abuse, and official misconduct—and I see no need to eliminate our state’s mandatory penalties for terrorists, rapists, and corrupt politicians.

"And, we will continue to aggressively pursue the most violent and dangerous drug criminals — like those operating the deadly opioid mills we recently dismantled in Harrison and Irvington. But that doesn’t mean we can’t recalibrate our sentencing laws when it comes to the mostly-young, mostly-minority non-violent drug offenders that fill our state prisons," Grewal wrote.

Calling Gov. Phil Murphy "a true advocate of progressive change," Grewal said he's proud of the governor for reconstituting the Criminal Sentencing and Disposition Commission to study potential reforms and make recommendations for new laws, as sentencing reform requires legislative action.

In 2009, the Legislature established the 13-member Commission. But, under Gov. Chris Christie’s administration, members were never appointed.

In February 2018, Murphy appointed former Chief Justice Deborah Poritz and Jiles Ship.

Grewal said he believes the commission is working toward a September deadline to share an update on their work.

"Now more than ever, the credibility of our criminal justice system is under attack, and the best way to restore the public’s confidence in this vital institution is to ensure that it works fairly and effectively for all members of our society. So let’s reform our state’s drug sentencing laws," Grewal said.

More from WOBM:

More From Beach Radio